Why Texas needs a recession-proof school finance system

Photo by Todd Wiseman

Why do higher-poverty school districts in Texas receive less funding per student than lower-poverty districts?

A new policy brief from the Center for Education Research and Policy Studies at the University of Texas El Paso College of Education, where I work, shows that gap to be 11 percent. The idea that higher-poverty districts receive less funding is not new, but what's missing from current policy discussions is why.

Much of the current funding gap has resulted from how the finance system responds to economic recessions. After the Great Recession of 2008, Texas initially relied on additional stimulus funding from the federal government. When those funds ran out in 2011, Texas cut K-12 education budgets by $4 billion. Legislators decided to cut evenly for the first year and protect high-poverty districts in 2012-13.

Unfortunately, according to our research, high-poverty districts still incurred a disproportionate amount of funding cuts. This funding gap between rich and poor districts grew by more in Texas than in 43 other states.

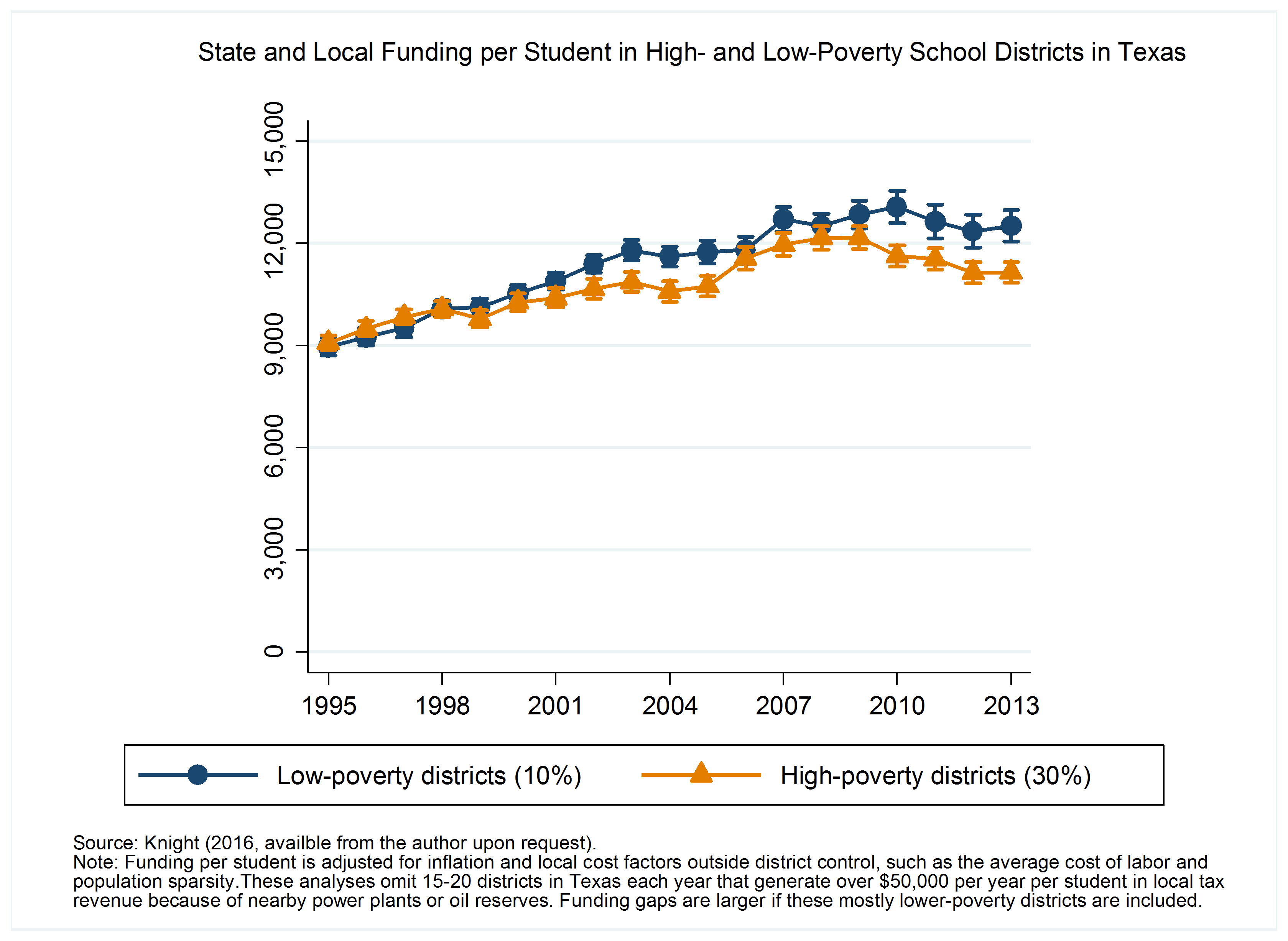

The graphic shows how the funding gap in Texas has changed over time. The figure plots the adjusted state and local funding per student for districts at roughly the 10th percentile of poverty (i.e., districts where 10 percent of its students are living in poverty) and districts at roughly the 90th percentile of poverty (i.e., 30 percent of students in poverty). During the years leading up to the recessionary spending cuts, the gap was narrower — about 2.7 percent.

By 2012-13 however, the gap between rich and poor students expanded to its current 11 percent. High-poverty districts in Texas now receive less funding and spend less per student, have lower teacher salaries and have fewer teachers per student than otherwise-similar wealthier districts in the state.

This funding gap is not the result of lower property taxes in high-poverty districts. In fact, high-poverty districts levied higher tax rates than their wealthier counterparts and increased their local tax rates at a faster rate following the Great Recession. The problem was that wealthier districts experienced greater increases in local property values per student and passed more bonds — and bond money is not equalized in the same way by the state.

The current funding gap reduces to 5.5 percent when accounting for federal funds, but this gap still has real consequences for students in Texas. For example, a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research recently found that a low-income student exposed to a 5.5 percent increase in funding for all 12 years of public schooling would experience a 6.3 percentage point increase in their likelihood of graduating high school, a decrease in their likelihood of living in poverty by about 5.4 percentage points, and an increase in adult lifetime earnings of about 14.4 percent.

The findings of our study come as legislators in Texas are debating how to reform the school finance system. A recent Texas Supreme Court opinion ruled the state's finance system was constitutional but outdated, overly complex, and “byzantine.”

Policymakers are now debating how to reform the finance system in preparation for the next legislative session in January 2017. Conservative lawmakers, under the direction of Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, are exploring mechanisms to tie funding to student test scores and other estimates of school performance. Schools would lose funding if their students do not score higher on state tests.

Yet study after study has shown that performance-pay policies for schools or teachers do not improve outcomes and do not make schools more efficient. Worse, these policies can remove funding from the schools that need it most — those serving greater proportions of students in poverty and students who are learning English.

Instead, the state needs to redesign the finance system so that it distributes funds more equitably across districts. Certainly, ensuring that new funding is allocated to effective, evidence-based programs is also critical. However, without legislative action to restore funding in the highest-need districts, the disparate impacts of the Great Recession school budget cuts will have real consequences on the lives of students.

More broadly, the CERPS study shows that school finance policy discussion needs to consider more than current funding levels. Another key question is how the finance system might respond to the next major economic recession — and which districts will bear the brunt of budget cuts if they are enacted. Legislators should consider provisions that would protect the highest-need districts from future economic recessions.

For a copy of the CERPS policy brief, please contact the author at [email protected].